The Clark Kerr Campus at the University of California, Berkeley, is a sprawling Spanish-style complex perched on a hill overlooking the bay. It was once the site of the California Schools for the Deaf and Blind, institutions that embodied the state's progressive ideals at the turn of the 20th century.

By the time I arrived as a freshman in 2007, the campus had been absorbed into the ever-expanding realm of the university. Now, it was a dorm—its history reduced to a few plaques and fading photographs. Kerr, the visionary UC president who had built Berkeley into a citadel of higher learning, was now merely a name on a building, consigned to the footnotes of history. His unceremonious ouster by the Regents in 1967, amid the tumult of the Free Speech Movement and the Vietnam War, marked the end of an era. It was the moment when the dream of California as a land of boundless possibility began to fray.

I had little idea then of the storied past I was stepping into, the grand visions and bitter disappointments that lay behind the stucco walls and red-tiled roofs. I was walking into a story that had already been told.

My first Fall term in Berkeley had a whiff of the 60s about it - the newfound freedoms and sense that consequences were for other people. But by spring, a dull torpor had set in, a realization that perhaps we were just going through the motions, playacting at rebellion and reinvention.

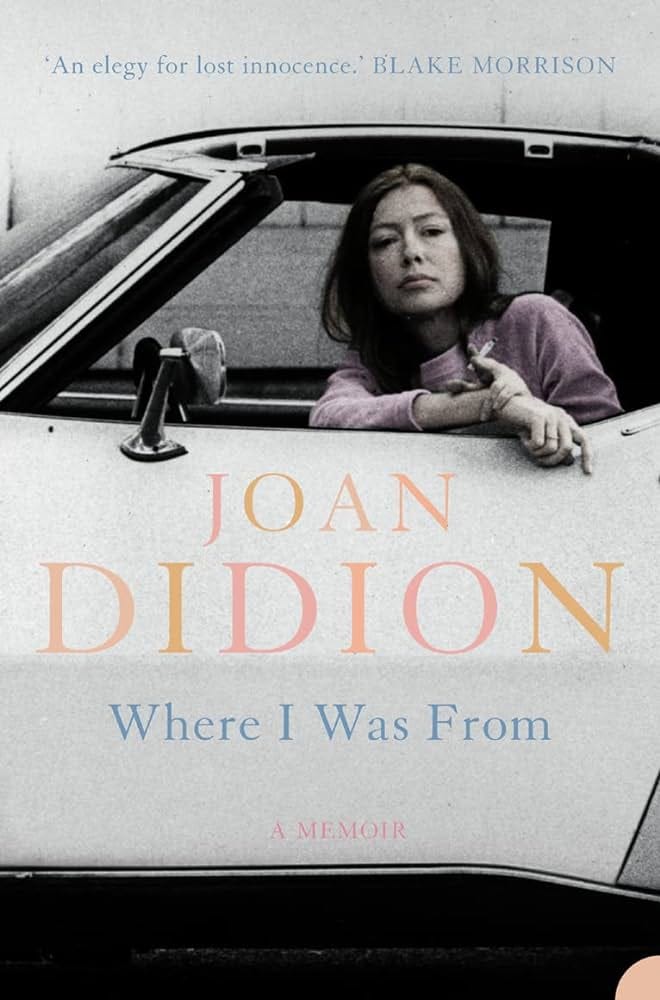

It was in this fog of disillusionment that I first found Joan Didion. I was hungover and washed out from a night of partying, the sun too bright as I stumbled around the Clark Kerr Campus. Her book Where I Was From turned up on a bench, left behind by some unknown hand.

Something about the title, with its hint of dislocation and self-inquiry, spoke to me. I picked up the book and spent the next few days immersed in Didion's razor-sharp prose, her unflinching examination of California's history and her own family's place within it.

Reading Didion was like having a veil lifted from my eyes. She wrote about the Golden State not as a paradise but as a place of contradictions, where the dream of the good life was underlaid by a sense of uneasy emptiness. Her essays were spare and unsparing, cutting through the haze of nostalgia to reveal the hard edges of reality. I had never encountered writing like this before—writing that made no attempt to comfort or console, but instead insisted on staring directly into the void.

That encounter with Didion planted a seed that would bloom into my own writing ambitions. Over the years, I found myself returning again and again to the themes around California she had laid bare—the dream and the disillusion, the gap between the shining promise and the shadowed reality. When the rise of “large language models” opened up a new frontier of AI-assisted writing, it felt like an extension of that same story—a fresh incarnation of the old California dream, ripe with both potential and peril, and a new set of promises and possibilities to be interrogated.

The Power of "In the Style Of"

Last year, as I began to play with with Claude—the ChatGPT competitor made by Anthropic—I discovered a simple but potent prompt that allowed me to channel my literary inspirations with uncanny depth and precision:

"In the style of [writer]."

With those five words, I could tap into the voices of my literary muses, absorbing their techniques and sensibilities in ways that felt uncanny.

There is a misconception that prompt engineering, the art of crafting effective inputs for AI language models, is a complex science requiring advanced technical skills. But in my experience, it is more a matter of artistic instinct. The best prompts for writers are not the most elaborate or specific, but the ones that capture something essential about the desired style, tone or objective in a few choice words.

When I whisper "In the style of Didion" to an AI language model like Claude, I am not just asking it to mimic her sentence structure or vocabulary. I am invoking a whole way of seeing the world - that unflinching gaze, that refusal of sentimentality, that sense of the precariousness of all human endeavors. Claude, having ingested Didion's oeuvre along with vast swaths of human knowledge, can reproduce not just her writerly mannerisms but the very shape of her thought with their complex “auras of meaning.”

To see one's own half-baked ideas return in the cadences of a revered master is a heady and somewhat unsettling experience for a writer.

But it is also generative, a way of breaking through creative blocks and accessing new registers of expression. By trying on the styles of different writers, you can expand your own stylistic repertoire, absorbing their insights and techniques into your own voice.

"In the style of" prompts grant us a kind of literary apprenticeship, studying at the feet of the greats even in their absence. They make the act of influence visible and tangible, a matter of conscious choice rather than unconscious osmosis.

An Antidote to AI's Blandness

Of course, to wield this power effectively requires discernment and control. It is all too easy to let the AI's fluency lapse into mere pastiche, a patchwork of imitative tics without any underlying coherence. The goal is not to produce a slavish copy but to use the master's voice as a starting point for your own explorations, a way of seeing through their eyes before turning your gaze in new directions.

In my own invocations of Didion's style I have tried to enrich but not erase my own voice. In the process, I have come to understand writing as an act of haunting, a way of communing with the dead that is also a way of keeping them alive.

In the age of AI, this spectral dimension of writing takes on new layers of meaning and possibility. With a well-crafted prompt, we can summon literary masters, making them speak to our present moment in uncanny new ways.

But why, in the vast sea of literary voices, do I find myself so often reaching for Joan Didion? It's not just the cut-glass precision of her prose, though that is part of the appeal. In a time when so much writing, human and machine-generated alike, feels focus-grouped and sanitized, Didion's voice stands out for its uncompromising clarity, its refusal to sand down the sharp edges of perception.

Too often, the output of language models like GPT is bland and generic, designed to offend no one and enlighten no one. It's writing optimized for engagement but devoid of any distinct style or point of view—the verbal equivalent of a stock photo or elevator Muzak.

To combat this, we might be tempted to give the AI detailed instructions, to micromanage its every move with injunctions to vary sentence length, to show not tell, to avoid cliché. But faced with such directives, the machine often flails and stutters, uncertain of its own voice and purpose.

The beauty of "in the style of Didion" is that it bypasses this problem entirely. Those five words carry within them a whole philosophy of writing, a set of aesthetic and moral commitments that guide the AI's hand without constraining it.

When I invoke Didion, I am giving Claude permission to be opinionated, to eschew the safe middle ground in favor of bracing truth, to adopt her stance of unflinching lucidity in the face of the world's chaos and contradiction.

Didion's style is characterized by an economy of language, a refusal of ornament or excess. Her sentences are often short and declarative, stripped down to their essential components. But beneath this surface simplicity lies a deep attunement to the detail that reveals whole worlds of meaning—the unspoken currents beneath the surface. The result is writing that crackles with insight and specificity, that feels born of a particular consciousness engaging with the world in all its messy complexity. It is the antithesis of the flattened, homogenized language that so often characterizes AI-generated text—a voice unafraid to be itself, to speak its mind even when it might be met with resistance or incomprehension.

Wielding Voice Mimicry Wisely

As AI language models become more sophisticated, distinguishing between human- and machine-generated text grows increasingly difficult, raising thorny questions about authorship, authenticity, and the potential for abuse. We've already seen AI-powered voice mimicry used for nefarious purposes, like "deepfakes" that put false words in the mouths of public figures. Similar techniques could easily be used to impersonate real people in text, whether for fraud, harassment, or political manipulation.

As writers, we have a responsibility to use these tools ethically and transparently, making clear when we are borrowing or remixing the voices of others and crediting our sources appropriately. (Have you figured out yet whose style this article is written in?)

At the same time, the creative possibilities opened up by AI voice mimicry are too powerful to ignore. By inhabiting the voices of our literary heroes, we can find our own voice by trying on the voices of others.

As I continue to experiment with these tools, I find myself wondering if they might offer a way out of the creative stagnation that often plagues the world of online content creation. In a world increasingly dominated by algorithms and SEO-driven writing it is easy to feel like we are losing touch with the authenticity that makes great literature resonate.

I wonder what Didion herself would make of all this. Would she be appalled, seeing it yet another Silicon Valley folly? Or would she be intrigued by its potential to reveal new truths? I suspect she would cut through the hype and zero in on the essential human questions at the heart of this technology. Perhaps she would see in AI a tool for interrogating our own nature, for understanding the stories we tell ourselves and the voices we allow to speak through us.

As Didion wrote in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, "the ability to think for one's self depends upon one's mastery of language."

As our language is increasingly mediated by machines, the definition of mastery takes on new dimensions. It's no longer enough to know how to write; we must also know how to prompt, how to curate and refine the output of language models to serve our own creative ends.

The rise of AI will fundamentally change the way we teach writing, demanding a shift from the myth of solitary genius to a more collaborative model open to the interplay of mind and code.

But even as we grapple with these changes, I find myself returning to the deeper lessons of Didion's work—the need for clarity, for honesty, for writing that cuts through the noise and illusion. These are the qualities that give words power. And they are the qualities we must cling to as our literary landscape evolves.

The promise of more humane language models like Claude points towards a different future - one in which the machines we create are not cold and calculating but warm and sympathetic, attuned to our own artistic sensibilities and capable of genuine collaboration.

Or maybe my inner California utopian is just spinning visions of a future that will never quite arrive— allowing Claude’s seductive fluency to carry me away on flights of unearned lyricism.

Didion would no doubt have something to say about that, too.